The Secret Protest Screening ethnographic project – part 1

September 8, 2015 § Leave a comment

I’ve spent a good portion of the summer being frustrated by the folks at Secret Cinema (London)–for reasons best left unsaid.

But then last night I get this:

For reasons of professional interest (the expansion of cinema, fictional presences in everyday life, etc.), I’ve been on Secret Cinema’s mailing list ever since we moved to London. I’ve never been to any of their events — but, surely, this has got to be the one.

And so starts the ethnographic project.

Query: why would people choose to express a protest by going to a movie? a movie they don’t know anything about? in a location they don’t know anything about? How does any of this make any sense, in the face of the plight of the 20 million or so refugees worldwide–or the plight of the more recent ones Europe has been struggling to welcome?

Method: audience ethnographic project. I will embed (with my 15-year old son!) within Secret Cinema’s audience for the evening, and conduct a field investigation. The trick, as usual with ethnography (at least since Malinowski!), is that this will perforce be participant observation.

And so the ethnographic project really starts with a research diary: what is my trajectory from non-audience to audience and back? What discourses are framing my attendance? What expectations do I bring? What representations are shaping what I think I will see? How do I construct what hypotheses? And what am I to make of the show?

This is what this diary, over the next 5 days, will trace: my trajectory to the film (or is it a show?), during the performance, and after it.

Monday 7 Sept. 18:21 — reception of Secret Cinema’s commercial email.

My itinerary, my transformation from individual to audience member, to vibrating aesthetic subject (or to commercial subject blindly manipulated, as you wish) really starts as I receive Secret Cinema’s email. (Well it really started earlier, a long, long time ago in fact, but 1) there is literally no end to that regressus ad infinitum and 2) the notes below will indeed elucidate some of what has been building in my trajectory before that commercial sollicitation)

I am sitting at my computer, it is evening, I’ve worked all day at the computer but I should be doing more–I’ve been frustrated over the past couple of hours that I haven’t been able to work as I had planned. There’s an article that needs revising, the deadline is in 3 days. But I’ve had to deal with minor domestic crises (no ink in the printer! No phone service!)–and so I’ve ended up nervously checking The Guardian‘s website for the 1000th time today (like everyday). In terms of me being turned into an audience for entertainment, I should note that this message also comes at a point where we’ve talked, as a family, about our frustration of not doing enough shows, museum visits, films, etc., in London. We want to “make more” of the city. We want, in other words, to become cultural consumers.

I think frustration is a keyword here.

This email attracts my attention for several reasons:

1) I’ve been trying to get more involved to help refugees over the past week — I’ve been trying to get more involved with border issues for months now, in fact I’ve pretty much decided that understanding open borders is what I will be doing in terms of publishing in the next 2 or 3 years. I have several book projects on the topic of borders already in my mind. But getting to do something concrete, useful, apart from sending money…it’s been difficult. At bottom I think I am afraid of contact–in the sense that I overanalyse contact with refugees as being contact with the great unknown, and I am a control-freak. It’s stupid and I hate it, but the reality is this: i haven’t been to Calais, to the Jungle, though I’ve read and crossed it several times (even saw police chasing the people there one night waiting for the Eurostar). I have signed up to help refugees in the UK, though I don’t have a spare-room. I have signed petitions, sent tweets, liked FB pages…but nothing approaching contact.

2) I am disgusted that the UK is not opening its borders to more refugees. If Germany can take the equivalent of 1% of its population (800,000 over one year), so could the UK (this would be 650,000….not the miserable 20,000 over 5 years that the Conservatives have promised today…better than nothing, sure, but paltry). And so the urgency of expressing outrage publicly, as inefficient and self-centred as it may very well be, has been building. I want to put public pressure on governments to do more. “Standing-by” is not an option. But see 1)…. Still, this promises to be a public event.

3) I am indeed intrigued by the concept of a “Protest Screening”. When was the last time attending a movie was a civic gesture? I can count on one hand the films I have seen out of civic duty: Lanzman’s Shoah in a Paris theater, or that documentary about Yitzhak Rabin that I saw in a small downtown Los Angeles theater (was it this film?). These are films I felt I had to make a public point to see–a duty to watch. But here I don’t even know what film they’re going to show us!

So the best I can understand my motivation is,

1) that I feel I have a duty to signal my participation publicly–and indeed, as soon as I buy the tickets, I invite a few London friends via FB to do the same–although there is an added sense of potential danger as I don’t know whether the film will please, shock, move, or disgust me. So, metaphorically speaking, I am willing to be potentially emotionally tossed around (yes, this is a boat metaphor, and I am aware of the creepy link with refugees, but at this point, I wouln’t put it past Secret Cinema to have worked out that metaphor themselves, see the poster for the event). And

“Aren’t you a little short of storm troopers?” asks a pesky FB user

2) that this is the closest I will ever be to doing something together with refugees: I am particularly attracted by the promise that the film will also be shown, at the same time, to the migrants stuck in the Jungle camp in Calais. Yes, this will merely be a virtual connection (in 3 hours there is no time even for Secret Cinema to transport us to Calais and back…), but we will share, and share emotions which is what humans can do. And, to be honest, this doesn’t happen every day at the movies nowadays: audiences, the general claim goes, are fragmented (by age group, sociology, ratings, etc.), and the days of the “evening’s entertainment”, with everything for everyone in the family, are long gone. This promises to create an audience more diverse than we’ve become accustomed to, and isn’t that what cinema is supposed to do best, help us connect, the Esperanto of film, film language as universal language, and so on? Secret Cinema, bringing you face-to-face with fiction..

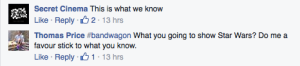

The nagging suspicion I have, so far, is that of course this is all commercial ploy. Secret Cinema has been trying to position itself as the rediscovery of the joy of cinema — a new Hollywood, as their cover photo of Aug. 21 intimates — and this re-creation of a common civic audience beyond differences (them and us, this side and that side of the border, poor and rich, etc.) smacks of a similar commercial positioning. Also I am not entirely at ease with a for-profi, commercial private company doing politics. The event Facebook page has been posting pro-refugee messages and promoting a very clear, astonishingly (for a private company) aggressive activist stance on the issue–but only since Sept. 2, the day news outlets published the picture of Aylan’s body on the beach: how long has Secret Cinema been supporting the Refugee Council? I can’t say. Are they seeking to exploit this tragedy? I can’t say. And I can’t say either how different this social media build-up is any different from their standard operating procedure and the FB build-up to their summer Star Wars show, for instance. Are they just trying to “put me in the mood”? Am I even supposed to enjoy myself at this show?

At the same time, for any company to take a political stance is gutsy–and sure enough, Secret Cinema is getting negative comments from FB users (“stick to what you know”)– but is this also staged? Is it just a ploy to allow them to answer “this is what we know”, so me, reading this exchange, will feel understood in my sympathy for refugees, immersed in a well-meaning and shared space of love and understanding for refugees, a space where I can abandon myself to emotions of pity, gratitude, etc., without a hint of critical disturbance, without, for instance, the dissonance created by this FB user’s ironical question “It will be interesting to see if this tempts any of the people in Calais to hang around there for the rest of the week so they can see the film, or will they try to illegally jump on the back of a lorry in the hope of being in London in time for the UK screening” ?

but is this also staged? Is it just a ploy to allow them to answer “this is what we know”, so me, reading this exchange, will feel understood in my sympathy for refugees, immersed in a well-meaning and shared space of love and understanding for refugees, a space where I can abandon myself to emotions of pity, gratitude, etc., without a hint of critical disturbance, without, for instance, the dissonance created by this FB user’s ironical question “It will be interesting to see if this tempts any of the people in Calais to hang around there for the rest of the week so they can see the film, or will they try to illegally jump on the back of a lorry in the hope of being in London in time for the UK screening” ?

And so I end up signing up for a host of reasons, but one of which harks back to the best Barnum every did: is it truth, or fiction? Reality, or a hoax? And, honestly, I can’t decide.

Ballyhoo ain’t dead — the research project

January 24, 2014 § 1 Comment

One of the fun things about studying things historically is to realise how modernity is laced with the past — intersected, habited, haunted. Not in the sense of plus ça change, more in the sense that the “new” carries with it undertones of leads already explored, of thoughts already spoken, of directions already tried — in a quasi-biological sense. The now, in science-fiction terms, is merely one of the possible futures that the past has developed — but it bears the traces of what might have been — tantalising, inviting us to invent tomorrow.

So we now call it “viral marketing”, or even “prankvertisement”, but it is ballyhoo back from the 1920s, promotional stunts that are meant to get people to talk about the film, at all possible cost. And just like ballyhoo, it is, at the very least, about rehearsing audiences’ media competencies — working on that border between the fake and the real, helping them (us) put reality in play. This training of media competencies, then, goes back a long way — the “magic” of new media technologies more a skill we entertain than an innate quality of any medium. Viral marketing, then, takes the Barnum hoax (Barnums’ “operational aesthetics”) to new, more modern, heights: “is it fake, or is it real?” It is the same question, it is the same game — but realising that we’ve been playing this game for at least 200 years (much, much longer than that: since the first time a human decided to make-believe that any piece of unbelievable information relayed in some form, oral, painted, etc., was potentially true) may help us enjoy it more — indeed, help us live with media fictions.

At most viral marketing (just like 1920s promotional stunts, though the technology, then, was different) asks hard questions about the nature of film-going, since it can be about transmedia storytelling expansion, furnishing bits of information to the main movie plot that help make sense of the movie world and expand it — hard questions about where the pleasures of “cinema” precisely lie. You may, for example, have felt (as I did) rather unsatisfied with the restricted world-building that the movie Elysium offered, notably the limited views of both Earth and the space station for the rich,

the way the movie restricted all economic activity on Earth to Matt Damon’s character’s factory job or his sweetheart’s nursing job (an economy based on just those types of low-skilled jobs would very soon crumble: what of the research, innovation, engineering jobs? How do these professionals feel about inequalities? About Elysium? How do they vote? These are all world-building questions, and what good sci-fi should be about as it attempts to build a model of a possible future). Indeed, it may be because that world-building was going on somewhere else: on the official website for the movie (www.itsbetterupthere.com), where there is[still, as of 24 Jan. 2014, but for how long?] a rich array of websites pretending to be from the construction company of the space station, complete with set-drawings blueprints of the homes one may “buy” on Torus. In lots of ways, the world-building that goes on with the promotional websites is more interesting than the movie itself — conventional, déjà-vu plot-driven fast-paced flick. And this raises the question, at least to me, of whether the film is not suffering from the fact that a decision was made to outsource lots of world-building material to the promotional campaign. Think about all the detailed world-building that went into the film itself of 2001, and made the experience of watching the film truly mesmerising. You’d have to start toying with the Elysium website before you’d start feeling the same level of amused amazement, the desire to stay in that world.

Incidentally, if the marketing is part of the fun of the film, it also raises the question of what happens to the film once that promotional material is gone (the anti-segregation blog “set up” by alien Christopher Johnson, a promotional stunt devised for District 9, for instance, has been archived, but the official link is dead) — and whether a true artist of viral marketing should not expand efforts into maintaining the fictional worlds they have set up for the film. Whether or not this would make any business sense, for the artist, would hopefully be irrelevant, though this points to a potential site of tensions here: the long-lasting relevance of a work, or the short-term, but powerful, vibration of meaning of a work encountering an audience? What if the second burst, though ephemeral by definition, could be made to last? A film like 2001 has no problem recreating its own flash of relevancy for a modern audience–but couldn’t there be another path to artistic longevity that promotional stunts, allied with new media tools, fast-speed networks, virtual reality equipment, and so on, could trace in the future of the industry? Prometheus may have been a disappointing film (haven’t seen it), but the website still looks good, inviting, tantalising — magic of sort, yes.

Prometheus may have been a disappointing film (haven’t seen it), but the website still looks good, inviting, tantalising — magic of sort, yes.

All of which makes me wonder if there is not more creativity being now expanded into the promotion — and less into the films themselves — and if the true evolution of transmedia storytelling is not just that the film fictions expand into other media, or that the films serve merely as events to launch a new line of merchandising, toys, TV series, and other products, as we are all quite aware — but that, more profoundly, the films serve as launching pads for the true fictional life of the stories that indeed take place somewhere else, in the promotional stunts. That the film becomes, in other words, a fictional virtual space more than a text. That maybe we need to think about a future where the film is reduced to a clickable link (“You Don’t So Much Watch it As Download It”) on a website where lots of other material build a detailed and amazing fictional world — where the film is one possible activation of the fictional world, which remains however open to other narrative possibilities through the world-building the websites offer. Given that promotional budgets may come to dwarf production budgets, this would not be such a surprising evolution after all–an evolution where film, “cinema” as we used to call it, expands its “interface” from a screen (a movie screen at first, a TV screen next, a mobile screen now) to a space (cyberspace, virtual reality).

The research project: to trace the development, history, genealogy, variations, evolutions of ballyhoo, promotional stunts, prankvertisement as the interface of cinema — from 1920s carnival to Torus, as cinema’s privileged world-building tool, en route to our future(s) where living with virtual realities is going to be loads of fun.

Ballyhoo definitely ain’t dead

January 19, 2014 § Leave a comment

and what’s more it’s still as controversial as ever.

http://www.thehollywoodoutsider.com/devils-due-best-promotion-ever/

and

http://www.devilsduemovie.com/convert/

Ballyhoo ain’t dead — another research project

January 8, 2014 § Leave a comment

A study of ballyhoo, from the 1920s to today (the Carrie stunt at a New York café, october 2013):

- a resurgence today, after decades of marginalisation of ballyhoo promotion to “disreputable” exploitation movies?

- if so, why a resurgence in new media today? Are we re-discovering a sense of media magic due to new technologies?

| Sent from Evernote |

The Reel Journal 1925-1926

August 31, 2011 § Leave a comment

Just stumbled across this online version of the The Reel Journal (1926), self-described as “The Film Trade Paper of The SouthWest”, and which seems heavy on the Kansas area. Of course, one could always go to boxoffice.com, since that’s the name under which this magazine is published today: its vault is free of charge and copies can be PDF downloaded.

Just stumbled across this online version of the The Reel Journal (1926), self-described as “The Film Trade Paper of The SouthWest”, and which seems heavy on the Kansas area. Of course, one could always go to boxoffice.com, since that’s the name under which this magazine is published today: its vault is free of charge and copies can be PDF downloaded.

media consumption

October 20, 2010 § 1 Comment

We’ve all seen this :

But why is it taking so long to go from boobtube to Youtube ?

But why is it taking so long to go from boobtube to Youtube ?

Film Publicity and Politics, 1920

April 30, 2010 § 2 Comments

Harry Reichenbach, on the existential link between new media and modern politics:

“Do motion pictures have to be advertised in this extraordinary way?”, asked the District Attorney.

“I will answer that question in this way, judge,” replied Reichenbach. “You take Governor Cox; he is running for President. Well, you see pictures of him in the papers cooking in camp; you see pictures of his wife cooking doughnuts, and you see his son riding a bicycle.

“Now, what has that got to do with his ability to be President? Nothing. But people will be attracted by that sort of stuff, and that is why it is put out. It is the same kind of press agenting that is put across for the movies.”

(NYTribune, 30 juillet 1920)

Channeling his inner Barnum

April 26, 2009 § Leave a comment

Do you believe in the reincarnation of Barnum ?

Advertisement for the Feejee Mermaid from the Charleston Courrier, Jan. 1843 (Museum of Hoaxes online)

These are two publicity stunts suggested by publicity material (from the great Kino 3 dvd set):

Do you believe a man beaten unconscious, frozen into an iceberg, and hewn therefrom a century afterward, with animation suspended, can be brought back to life?

and

As Houdini in The Man from Beyond is first disovered in a mass of ice on board a derelect barkentine, a lobby display might be arranged with a fish frozen in a cake of ice. The placard on the ice can read: “The Man from Beyond slept in an ice prison for a hundred years but was restored to life. He will be inside this theatre (date).”

Feejee Mermaid, anyone ? Or, as Barnum (in Neil Harris’s Humbug) would ask: “is it real, or is it humbug? You decide.”

questionable taglines: 1922

April 25, 2009 § Leave a comment

The Man From Beyond, Houdini’s latest photoplay, pictures the romance of a man of 1821 for a girl of 1922.

talk of a June (1820) – September (1922) romance

Released today: The Little Minister (1921) – the Christmas edition

December 24, 2008 § 1 Comment

Stanlaws in his studio, 1955

When looking for films officially released on Christmas Day in the 1920s, one faces an awkward choice: Should it be Flesh and the Devil (a personal favorite) or Curtiz’s The Third Degree (a timely topic), both from 1926 ? A swashbuckling family romance (Regeneration, from 1923, which tells the story of a couple left on some uninhabited island they call “Regeneration”), or a romance of the French-colonized, Foreign-legion owned desert (A Man’s Past from 1927, with Conrad Veigt), or one of a myriad of small run-of-the-mill westerns (the alluringly-titled Land of the Lawless, also from 1927) ? A family drama from 1921 (Ashamed of Parents, where poor boy turned college footbal star is ashamed of his poor relatives) could be ideal for family viewing…But parents beware ! The family drama is a slippery category as Eden and Return, from 1921, shows. It has a promising title, but the plot turns around a rebellious girl who refuses her father-approved suitor for a flashy big spender who regains his fortune by stealing stock market tips from his father-in-law ! Ah, the stock market really brings out the best in people…

One thing is clear: there is no Christmas pattern here. One reason for that is that the release date, as indicated on AFI records, does not necessarily coincide with the premiere date. But even when it does, there is still no Christmas pattern here, at least in the film plots. Consider Back Home and Broke, with a New York premier on 24 dec. 1922: featuring Thomas Meighan, it has an impossible story of a young man who goes West to make money through oil, then returns home and saves village business owners from the threat of a Mr. Keane. Not much of Christmas here (Regeneration, quoted above, is another example of a Christmas premiere with nothing of Christmas in it: it opened in Jacksonville FL on Dec. 24, 1923, but it’s largely a treasure island yarn).

So I’ve picked a very obscure film, offering a genre that is quite remote from us: the Scottish fantasy highland life. The film is The Little Minister, 6 reels from Famous Players-Lasky, directed by Penrhyn Stanlaws, with Betty Compson. Moving Picture World offers this plot summary:

“When the weavers of Thrums, enraged by a reduction in prices for their products, rise against the manufacturers, Gavin, ‘the little minister’ intervenes with the constables in their behalf. Babbie, a supposed Gypsy girl, is suspected of having notified the rioters that the police were coming so they might be prepared to fight, and a price is placed on her capture. But when Gavin questions her, her beauty and appeal charms him and he aids her to escape. A romance between the pair impends, much to the dislike of the elders of the Scotch kirk and Gavin is about to be defrocked when the Gypsy girl is brought into the meeting and discloses that she is in reality Lady Barbara, daughter of Lord Rintoul, the baron-magistrate of the district. In aiding the girl to escape Gavin had told the constables she was his wife, which in Scotland constitutes legal marriage if admittance is made before witnesses.” ( Moving Picture World, 7 Jan 1922, p112.)

Recommending it to our attention, the film was based on a James M. Barrie novel, then play (the novel is accessible through Google Books, here). This would be the same Barrie as wrote The Admirable Crichton (DeMille turned this into a statement on modern morals in his 1919 Male and Female) or Peter Pan. Childish romance, meet hard realities: a strike in Thrums is averted by the Minister but helped by a Gypsy girl who in reality is none other than some socially OK big shot…The pattern is well-known.

Stanlaws, it turns out, is quite a figure: a commercial artist who drew covers notably for the Saturday Evening Post, from 1913 to 1935 (and other similar proper publications),

he also had a very short lived (1921-1922) film career as a director for Lasky, and the vein seems to have been goody-two-shoes stories on par with his illustrations. Stanlaws had been specializing in genteel drawings of nicely behaved ladies since the late 1880s, and had made quite a name for himself (his illustrations are everywhere: Life, New York Times, Ladies’ Home Journal…): a 1903 article from The Atlanta Constitution, noting the illustrator’s desire to become a playwright (his first, one-act play, had just been taken up for production in London), reverently called him “the American depictor of pretty girls” and “the inventor of the ‘Stanlaws girl.'” In sept. 22, 1907, Stanlaws “gallantly leapt to the rescue” of the American girl, slandered by a Mr. Masson-Forestier, a columnist in the British Standard, who had claimed the American girl inferior to the Italian or the English in beauty, as judged by the paintings they all had inspired. Stanlaws was not amused, and concluded his defense with an interestingly proto-multicultural appeal:

Does M. Masson-Forestier believe himself to be a better judge of Japanese beauty than the Japanese? As for the Indian type, I wonder if M. Masson-Forestier has ever seen a Pawnee girl or a young Iroquois brave. (New York Times, 22 sept. 1907)

Quite a polemic, indeed. In 1913 the “American Girl” is back to the fore in a series of articles in the New York Times, for those interested. And in an interview to The Atlanta Constitution taken at the Famous Players Studio, Stanlaws decidedly assumes an air of knowledgeable authority over “the” American girl and her beauty thanks to a solid supply of meaningless clichés (“our modern woman has more in common with the great English beauties, etc.”) and has this to contribute to the motion pictures:

After waiting a moment I ventured to intrude with my next question, concerning Mr. Stanlaws’ aims in the moving picture industry, into which field he has but recently entered. What at first seeme da rather strange adventure on his part was defined more clearly as he talked about it. In spite of the marvels so far accomplished, the moving pictures, not as an industry so much as from the purely dramatic and artistic standpoint, are still in their swaddling clothes. And it is with this recognition that the services of such men as Barrie, Stanlaws and many others of dramatic and artistic note, to say nothing of the eminent actors from the speaking stage, are being enlisted, so that through the wonderful medium of the camera not only varied types can be introduced, but whole and successive stages of their lives and emotions, their manner of dressing and of behaving through all the stress and complexity of the manifold conditions of modern life.

Mr Stanlaws feels that the real American girl should be depicted more freely and more faithfully in the modern pictures. The Western girl, and that not as she is today but as she was thirty or forty years ago, has been done to death. Let the more representative girl take her place. And dramatist as well as artist, Mr. Stanlaws is putting all his artistic fervor and genius into the work of writing and producing and assembling the most realistic and the truest types of interest to the restless, exacting theatergoer of today. (Atlanta Constitution, 8 aug. 1920, p. 13)

Between Poses (1915)

Typically for the times, Stanlaws could both be a commercial artist purveying rose-coloured pretty girls for immediate consumption, and a realist. He’d already established this position through paintings such as the 1915 Between Poses. Frank light that avoids any hint of dramatic, hyped-up conflict, a simple background opening up into more space in back (not unreminiscent of sets that movies would come to use in the late 1910s), and its thinned-out, unclassical view of the feminine body (the arms are bony, the stomach is bulged), it has Eakins written all over it. The moment itself is a familiar trope of realist painting, debunking the tradition-sanctioned moment of the artistic pose by showing a scene taken in between posing sessions: a behind-the-scene type of look, so to speak.

Interestingly, the movies, in their quest for cultural legitimacy, were indeed hungry for whatever recognized artists such as Stanlaws or Barrie could offer in terms of marketing: the double promise of beauty and realism was, from a commercial perspective, simply irresistible for movie producers. It fit right in with the critical trope of the days applied countless times to movies, the infancy-adulthood debate. The nature of movies, a modern product, was to offer a modern view of modern life: technically deficient, the movies could only progress, “grow up”, and their nurturing would be provided by artists versed in the modern artistic schools of the theater or of painting: the realist and the beautiful schools. Stanlaws, as H.H.Hill makes clear, is a perfect choice for both (The Atlanta Constitution has the story, in Feb 12, 1922, of how actors on a Stanlaws production, Over the Border, were arrested by Revenue Agents who had taken them for real bootleggers. Their advice to Stanlaws: “not to be so derned realistic” the next time…).

Evidence that Stanlaws could read this game perfectly is shown in a 1914 interview from the New York Times: Stanlaws, based on his experience of drawing the portrait of Miss Norma Phillips (the Mutual Girl?) shows himself interested in the movies “as a means of spreading the desire and cultivating a taste for art”.

Stanlaws, the New York Times of 29 may 1920 notes, is “a native of Scotland”, so his selection for a Scottish story makes, for the time, sense. Though this argument only goes so far: Stanlaws’ first film for Lasky, At the End of the World, also featuring Betty Compson, took place in China. Still, the Los Angeles Times pulled it for its pre-release review of the film, noting:

It was peculiarly fitting that Penrhyn Stanlaws should direct this production, for he was born within a few miles of Thrums, and was reared amid the atmosphere which b arrie so successfully wrote into the play. The result of this knowledge, plus Stanlaws’s artistic perception, is an exceptionally beautiful production, which loses none of the homely humor and shrewd insight that originally made the play a success. Add to this the acting of Betty Compson, and you have what should prove a most appealing holiday presentation. (Los Angeles Times, 18 dec. 1921)

So it was a Christmas movie with Christmas on its mind, after all. I guess the formula hasn’t changed much: fantasy, Olde England, beautiful girl…and appropriate music indeed:

In addition to this feature picture, Sid Grauman has prepared a musical program that will harmonize with the spirit of the season, and numerous novelties also devised to promote holiday cheer. (Los Angeles Times, 18 dec. 1921)

While the music was probably heavy on carrols, the fact remains that the “holiday” in a “christmas” release did not have to be borne by the film itself, as is the case today, as the film presentation was surrounded by other media opportunities to fit the film within the calendar.

Still the film advertised its true-to-life documentary quality as it could. The Boston Daily Globe informed its readers (Dec. 25, 1921):

It was some search for a weaver in which the property department indulged when Penrhyn Stanlaws was filming “The Little Minister.” A loom was ordered by Mr. Stanlaws, and everywhere the property men searched before they at last found the required Scotch loom of the vintage of 1830 safely tucked away in the attic of a Los Angeles Scotchman. But no one knew how to operate that loom. For some days the scene was delayed, until the right man was found who could operate the loom and teach the actors how it should be done.

A story dutifully reprinted in The Washington Post of dec. 25, 1921, which had no qualm naming its review of the film “Scotland in 1830”. And The Chicago Daily Tribune agreed:

While it wasn’t made in Scotland, it is vurra suggestive of ye bonnie braes, so far as I can see (Never having been in Scotland). The photoplay has that intangible thing known as “atmosphere.”

The New York Times (dec. 26, 1921) approved of the “artistic” sets (“well-composed”, “pleasing as pictures, easy to comprehend with the eye”), but found the film too talky (“its dependence upon conversational subtitles”). But Robert Sherwood, in Life (Jan. 19, 1922), had no criticism for the film; Penrhyn Stanlaws the illustrator, however, came in for some characteristically Sherwoodesque fun:

Penrhyn Stanlaws has undergone a magnificent metamorphosis. When he was doing magazine covers a year ago, he was unquestionably a bad artist. In fact, he wasn’t an artist at all. He was a professional depicter of beautiful dumb-bells. Then he went into the movies as a director, and today he stands out as an artist, in a field where real artists are all-too rare.

“The Little Minister” is a work of art. Pictorially, it can be compared favorably with any motion picture that has ever been made. In composition, in lighting, in selection and construction of backgrounds, and in photography, “The Little Minister” is as close to perfection as it is possible for a movie to be. To eyes that are weary of looking at miles of harsh photography, crude, unintelligent settings and careless, uninspired composition, this picture is incredibly beautiful and soothing.

It is fine, too, from a dramatic point of view (…). The story is developed in simple and logical style in Edfrid Bingham’s scenario.

Was the film re-titled between Christmas and New Year ? Was Sherwood not as bothered by the dialogue titles, where the New York Times, in its highbrow fashion, would have placed the artistic bar higher, and in a more visual dimension, than Hollywood films were accustomed to ? The film, sadly, appears lost today.

(and that, folks, is all for 2008. I’ll see you all back in ’09 as I’m off to some skiing. Thanks and come back in January!)