In Quest of Sunken Treasure: Decorative TItles

May 28, 2014 § Leave a comment

from The Submarine Eye (Williamson, 1917)

A short analysis on this most forgotten art form of the not-quite silent movies, the decorated intertitle card, from The Moving Picture World, 26 May 1917 — proving, to boot, that not everyone in movie land was busy thinking about the war even then 😉

Silent cinema : the universal art ?

January 22, 2014 § Leave a comment

[UPDATE Jan. 22 2014: this was written back in July 28, 2009. Still worth a post I reckon, though the film referenced may be a bit obscure.]

Remember those ecstatic pronouncements of silent cinema as the New Esperanto ? Was going to save world peace ! Was going to make humanity One ! Would convert the Czar of all Russias to judaism (not really, just throwing this one in) !

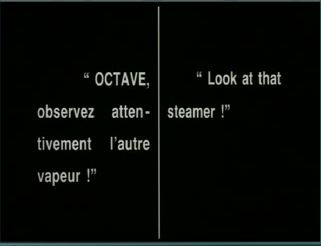

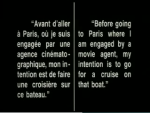

Turns out, this depends on where you’re sitting. If you’re from Hollywood, the world may have looked remarkably flat as early as the 1920s. But a Russian émigré living in France in 1920 may have had a different view : consider the titles from Jakov Protazanov’s L’angoissante aventure

Back to Babel it is with the pesky problem of the intertitles.

But it’s not just the intertitles that erect conventional barriers to universal meaning. I defy anyone outside of the tight-knit émigré circles of expatriate Russia to understand the man’s expression as he reacts to the woman’s innocuous enough pronouncement (granted, I haven’t seen the film):

I don’t want to think how Peoria, Kansas would have taken that look. Bottom line: there is not one universal meaning, or one universal audience, in films. Not then, and not now.

Words on images: the Olympic moment (1928)

July 2, 2012 § Leave a comment

Courtesy of the IOC YouTube channel, this thrilling 5,000 m race from the Amsterdam 1928 Olympic games features original use of onscreen titles — and therefore deserves to go into the series, started long ago here at flycz, that aims to catalog moments in silent films when words were flashed on images, as opposed to in-between.

The great Bioscope, to which, once again, I’m indebted for this examples of onscreen titles, informs us that this Olympic footage is part of the 1928 film of the Summer Games in Amsterdam, Olympische Spelen, the first Olympic film directed by a German director, Wilhem Prager with an already established reputation, and thus

Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia of 1936 was neither the first Olympic film nor the first with a notable director, as comes histories would have us believe.

The Bioscope notes that Prager’s film is

no more than efficient, though it does have some innovations such as having the names of athletes in some distance races appear as captions alongside them as they run.

Not for me to comment on the quality of Prager’s film, but on the “innovation” of onscreen titles, I’ll add my two cents: not only had Wilhem Prager already included onscreen titles identifying track athletes as they’re running in his previous kulturfilm sports documentary made 1924-1925, Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (Ways to Strength and Beauty) — a film I reported on here and here — but the practice of adding caption on shots of running athletes could very well have been fairly standard by 1925, as this other example from the US-produced The Plastic Age shows:

In other (bordwellian) words, we could very well have here a schemata: identifying running athletes, or commenting on a race, is recognized as adding drama to the images — yet interrupting the visuals of the race kills this drama, as the show is about watching people run. How to solve this conundrum ? By doing something usually not part of the canon. The impossible onscreen title, usually relegated to comic purposes on film for its link with comic book dialogue bubbles, becomes then possible, even necessary, and appears again and again (this is merely hypothesis and would need to be checked by viewing other 1920s sports documentary or fiction films). By 1928, it could be standard solution — standard, though Prager’s solution, to have it in one corner below the track, is the most elegant of all I’ve seen so far.

dialogue balloons – the cartoon take

July 29, 2011 § 2 Comments

An addition to the still ongoing series on words on the image theme we have here at flycz: the cartoon version. This is an example from Bobby Bumps, the 1916-1919 cartoon series from Bray studios (thanks to the Bray Animation Project) :

A simple solution to the inter-title problem, in line with other cartoon-based methods of commenting and orienting the action on screen used widely at the time — I’m thinking of the question or exclamation marks so frequent in more famous Felix the Cat series, or the literal eye-line used also in this same Bobby Bumps :

What’s odd is that earlier in that Bobby Bumps usual inter-titles are indeed used :

Does this incoherence reflect an ambiguous positioning of American cinema’s aesthetics circa the late 1910s as regards the inter-title issue and the whole question of allowing words to appear on the image ? Not that words on the image disappear later in the 1920s either, as we’ve started to document on this website (see here for a live-action example, there for another, later, cartoon example).

Titles and images on a silent image

August 1, 2009 § 1 Comment

Continuing this ongoing series dealing with the separation of written words and images (click on the intertitle tag below in the “What’s On” section). Was alerted today (by the resourceful Koszarski, An Evening’s Entertainment) to this passage in Lescarboura’s manuel on motion picture techniques first published in 1919:

A considerable amount of thought must be devoted to the audence’s understanding of the picture. The center of interest in a cartoon must always be played up prominently by subduing other features. For instance, if one of the characters throws a missile, it is necessary that there be no further movement of his arm after the missile begins to travel across the picture. The character–and every other character in the drawing, for that matter–must remain absolutely rigid so that the attention of the audience will not be distracted from the missile which at that moement is the center of interest. Then again, when a character is made to speak by the introduction of what is known as a “balloon” within which is hand lettering, there must be no motion in the cartoon until the audience has had time to read the legend which then disappears. (306)

Lescarboura is here talking about animation technique, an example of which could be this 1920 Mutt and Jeff cartoon (Mutt and Jeff Go on Strike) recently restored by a cooperation between the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia and the National Film Preservation Foundation, and which you can see online for free (also available on the same site, an alluring trailer for the 1922 Sin Woman in which she almost disrobes…need I say more?).  But I’m tempted to apply his reasoning to the apparent ban (not always respected, as I’ve shown in the above-mentionned series, but quite wide-spread anyway) on mixing titles with moving images in live features: words flashed would be too distracting (though distraction is not the taboo that some would have us believe in a Hollywood film…but I’m getting ahead of myself).

But I’m tempted to apply his reasoning to the apparent ban (not always respected, as I’ve shown in the above-mentionned series, but quite wide-spread anyway) on mixing titles with moving images in live features: words flashed would be too distracting (though distraction is not the taboo that some would have us believe in a Hollywood film…but I’m getting ahead of myself).

For curiosity’s sake, I’d like to read what Lescarboura thought of that 1920 experiment….

Why no words on images ?

July 12, 2009 § Leave a comment

The subtitle mystery continues.

This opinion in French from Alain Masson (L’image et la parole, 1989) : images + words written on separate title card = discourse recomposed in the spectator’s mind. Subtitles in silent films thus create a tension, threatening to empty images of their significance while being necessary to their intelligibility. Not sure I’d agree with this last sentiment, but I agree with the tension, though to me the tension is between an image where interpretation is free and subtitles that try to steer the film back to its narrativity.

In this view, words flashed on the image itself are either assimilated to visual signs (hence their use, mostly, in comic-style situations for cartoonish effects) or they totally cover up the image (in the documentary context). Flashed separately from the images, they help in the creation of a complex film discourse, heterogeneous, juxtaposed, unified in the audience’s perception only.

This tension goes both ways : it also raises the possibility that the image will surprise and not just fulfill the program announced by the subtitles :

d’abord, les intertitres. Ils précédent presque toujours l’événement ; ils sont rarement équivoques. Mais la netteté de l’annonce change l’illustration en variation ; sous peine de pléonasme, dans la séquence qui suit une légende, ce qui ne l’illustre pas prend la plus grande importance : la nuance indécise, non l’exécution d’un programme. (52)

Talking like comic book heroes

July 4, 2009 § 1 Comment

I’ve been looking for this for quite a while, and of course the information was right under my nose in a book I’d bought a while back but never actually gotten around to even open: James Card’s idiosyncratic Seductive Cinema. Here it is, then, the killer example of someone, in American cinema, trying to have titles flashed over the image of characters talking in a silent film: The Chamber Mystery, 1920, directed by a guy from Pinsk. Here’s what imdb.com has to say about him:

Abraham S. Schomer

Date of Birth

2 August 1876, Pinsk, Russia

Date of Death

16 August 1946, Los Angeles, California, USA

Mini Biography

One time leader in the Jewish Congress, Schomer was a well-known Yiddish novelist and playright. A New York attorney specializing in immigration law, he gave up his law practice in 1915 to write for motion pictures.

I’ve been on the lookout for instances of words used over photographic images as you can see in my series on Words over Images, but this is the purest example of a narrative use I have found – the other uses were more in pseudo-documentary contexts or in comedy situations where the comic book subtext was more obvious.

Carr offers this image  and adds that this was Schomer’s last film and the last time this experiment was tried. Was it ? I’d love to see other photograms of the film, and I’m happy to report that there is a three-minute excerpt of the film on DVD from Flicker Alley (Discovering Cinema, 2007) – along with some Caruso recordings that I’d very much like to get, also.

and adds that this was Schomer’s last film and the last time this experiment was tried. Was it ? I’d love to see other photograms of the film, and I’m happy to report that there is a three-minute excerpt of the film on DVD from Flicker Alley (Discovering Cinema, 2007) – along with some Caruso recordings that I’d very much like to get, also.

But was it the last time this was tried ? If so, why ? Is there some sort of ontological reason why written words could not be mixed with the visuals — an hypothesis that bodes well for the bifocal nature of Hollywood silent narratives : the text brings in another, often dissonant voice that never fully meshes with the visual flow and has always been described as a “problem” for silent film, even at the time, with the goal being that of the title-less silent film. That this ideal was rarely achieved in the 1920s (litterature always mentions the same two or three examples: Ol’ Swim Hole, Murnau’s Last Laugh…) is itself a tell-tale sign that this was an ideal but not a particularly important one from a concrete point of view of cinematic pleasure. 99.99% of silent films had titles, and not just because audiences (real or imagined by promotional campaigns) were “dumb”. I’d argue that titles, in their non-synchronic nature, because of the very nature of the juxtaposition and discontinuity they offered, were part and parcel of cinematic pleasure. Flashing titles on the image, from the point of view of narrative efficiency, is the smartest way to go: all the info one needs is given all at once. American cinema did not go that route, however, because narrative efficiency is not its be-all and end-all: the pleasure was (is) to experience the image and then to experience the often strong narrative voice that speaks through the titles, to feel that there’s a strong pull to bring the images back into a 19th century narrative fold, but that images always escape that fold, because they give out much more information and open themselves to all sorts of non-directed gazes.

In other words, the solution “titles on the image” was not long-lasting because it went agaist the fundamental heterogeneous pleasure of silent cinema, because it brought images down to a mere level of being a support for narrative information carried out through the titles. On their own, images were much more fascinating because they gave out (give out) much more than mere narrative information. In-between the images, the titles attempt to reimpose some sort of order on what promises to be an orgy of visual stimuli, with the audience granting, or not, the authority to do so to the written narrative voice – thus remaining on the edge, always, of narrative incoherence and madness. Just, you see, on the edge.

Putting words on the image 03 – “ethnography”

June 9, 2008 § 2 Comments

This is so far the earliest example of this rare practise in Hollywood silent films of having titles run on a moving image. It is from Terror Island (James Cruze, 1920), and as the titles dissolve on the shot the image shrinks noticeably:

Clearly an effort to throw a little documentary dust into the eyes of the audience. There really is no mistaking this for what it is, a straight out-and-out melodrama with little to none documentary value: are we in Polynesia or Africa ? What’s the feast about ? What “long pig that speaks” ? This is no “Paepae Tapu”: it’s flat and not a height by any measure — in fact it’s right there on the village center (so much for the “Forbidden” sacred spot). The “ethnic” part of the film is a simple and artificial foil for the hero (Houdini), and nothing more. The use of a quote from O’Brien’ 1919 White Shadows of the South Seas is part of that transformation of the documentary into spectacle that is so frequent in the literature and “documentary” filmmaking of the day.

But the titles dissolving on the moving image stand out: they are a visual quote of more precisely documentary formats, and as such, it’s an interesting little technical twist, almost an aesthetic attempt to give more legitimacy to the scene.

putting words on the image – 02

May 21, 2008 § 2 Comments

This is a series that started long ago here and then rebounded here, but this is its true second installment.

This is an example of words written on a moving image, in this case the runners in the background:

This is from The Plastic Age (1925). I’ve seen this done before, and in a sports context too: The Way To Strength and Beauty, that 1924 German film shown last year at Pordenone, had a few shots of track athletes, introduced with their names printed on their moving image.

So to conclude in this instance, the infringement of what seems usually like a pretty rigid rule (no words written on a moving image) gives a realistic, newsreel touch to the presentation.

A musical joke in a silent film

April 3, 2007 § Leave a comment

Yes, that’s possible: M’Liss (1918) has one: it allows the audience to perceive that M’Liss-Pickford sings Rock a My Baby off-key….without music ! Quite a trick eh ?